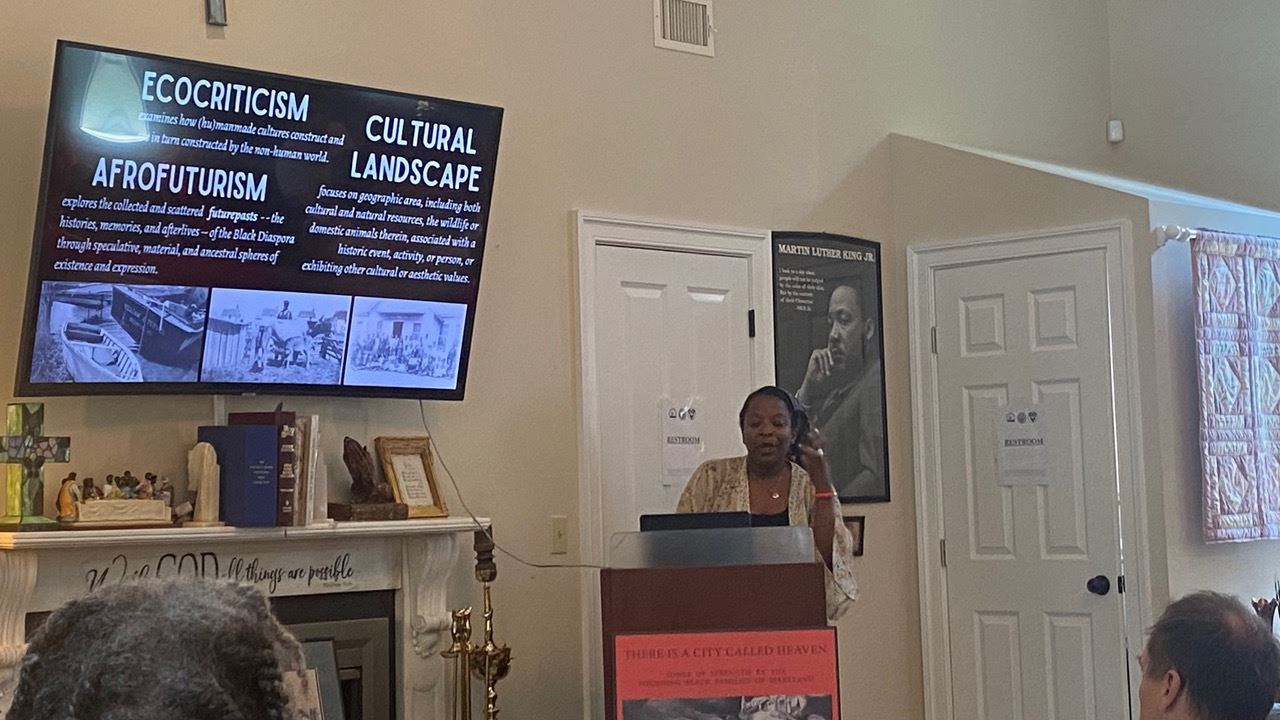

Ebram arrived late, bursting with energy. He and his team were recording an oral history and the community member had offered such a rich account of her childhood in Bellevue that they could not pull themselves away. I was already at the dinner table feasting on steamed shrimp and learning from students about their experience of the field school. A Women and Gender Studies PhD had some experience with oral histories but the long days measuring floor plans was entirely new. With her major in community development from Howard, another student reported that the field school was providing a set of tools she might use in her future work fostering healthy African American communities. The shy—and very smart—undergraduate student with a double major in anthropology and environmental studies saw immediately the benefit of a cultural landscapes lens and was really turned on to the idea that the living community can also be an historical resource. The conversation gently meandered among the students, each a bit cautious as they shared their experience with me, a total stranger. For most—but not all—of these students, this was their first year participating in the Mellon Foundation-funded “Black Life in Bellevue Field School,” run by Mike Chiarappa and Janet Sheridan in partnership with the organizing partners of the Bellevue Passages Museum. The field school’s primary goal was to document this historically Black waterfront—and waterman’s—community on the Maryland shores of the Chesapeake Bay to generate content for the intended museum. The summer of 2022 had focused more on mapping and building documentation, meeting the community, and spending a lot of time listening. This summer had continued the documentation work, but with a little more trust from the community, pivoted to include oral histories and more robust community engagement. During my visit near the end of the field school, conversations with community partners made clear that the intended goals of honoring local history and serving the community were being met. The field school had given the community the needed catalyst to move forward with the museum and to begin the process of applying for designation as an historic district.

While I met with Mike and Janet, and with community partners very pleased with the work, it was that dinner with the students that left the biggest impression. Ebram had bounded in with his two partners just behind, grabbed a plate of food, and sat at the other end of the table. Discerning the arc of the conversation, he waited for the appropriate moment to speak. Trained as a landscape architect, he came to the field school confident that he could offer his skills in reading and documenting the landscape. But he was entirely unprepared for the work of listening to community members, documenting unarchived histories, and learning to see the landscape through their eyes, with their historic sensibilities. This landscape was more than physical, ecological. It was also historical, cultural and social. In correspondence since the completion of the school, he described it as “transformational…[reminding me] that there is value in the vernacular.” “I am more motivated than ever,” he wrote, “to enter the conversation and contribute to moving the field of preservation in the direction of conservation and stewardship.” As he completed his summer and pivoted into his first year of the PhD, he now took with him a commitment to the patient work of earning trust and listening well. Even more, he was deeply moved by the idea that this was a community-led initiative. “I learned that we must go back and engage the landscape and its inhabitants to interact with ancestral wisdom, and once there, the wise will show you the way forward, but with words, so we must listen closely and meet them in their memories with maps.” While his previous professional training centered him as the expert, he found deeply humbling, and very moving, the idea that his role was to serve the community. Poetically, he argued, “I’ve been birthed into the old.” This student dinner reminded me of the importance of this work: of partnering with Black communities to elevate important but under-recognized cultural landscapes, and to train students into the commitments of careful documentation and responsible engagement with the communities that steward cultural landscapes.

Soon after I left, Jim Buckley arrived on site and soon after his return he shared that he “was struck yet again by the importance of the site, which is being lost to new development, and the impact of our students, which is tremendous. I happened to arrive on a day when a state commission on environmental justice and sustainability had convened in Bellevue to hear about the work of the VAF Mellon Field School. Each student presented some part of what they had learned about the project to the commission, but they were encouraged by the field school instructors to express themselves in their own way. As a result, their offerings included not just measured drawings and oral histories, but a poem about Bellevue, a fictional letter from one of the historic figures who had lived in that community, and paens to the trees and wild animals that have co-habited the site with the human community over time. One student wove an incredible story for us about deed research on a particularly interesting parcel, with an enthusiasm for ownership transfers and lot line adjustments I have never heard before. It seems to me that these students will be a transformational force in our field for some time to come!”

As the Bellevue Field School completed its second season, the John’s Island Preservation Field School finished its first. Run by Jon Marcoux and Amalia Leifeste from Clemson University in partnership with the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture and the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, the field school began by training students, many of whom had direct ties to the community, to read a historic landscape, undertake archival research, and also to listen to and document respectfully various community voices. This field school centered its work around two very important but neglected the early and mid-twentieth century Sea Island African American community hubs: the Moving Starr Hall and the Progressive Club. Both were sites of Black community life in the context of Jim Crow South Carolina. The field school included workshops on historic preservation, archival research, and architectural history documentation including measured drawings, laser scanning, photogrammetry, and GIS. I had the pleasure of visiting the field school in the closing week and had the great delight of spending the afternoon in the local public library listening to the students deliver the products of their work. Each student brought a different approach, asking different questions of the cultural landscape and its history. As with the students from Bellevue, these students came from a wide variety of backgrounds but their final presentations made clear that they had come to embrace the core commitments of cultural landscape research and documentation.

The third and final field school will be launched next summer by Jobie Hill, who was a contributing member of the education team at both the Bellevue and Johns Island field schools. Jobie’s school centers on the documentation of slave quarter sites at adjacent plantations in central Virginia, but, as with the other two schools, a close sense of partnership with the living descendants of the buildings’ historic inhabitants. Taking a long view of these buildings through time, the field school seeks to understand them not just as quarters for the enslaved, but also their use through Reconstruction and Jim Crow. The field school will also grapple with the questions of best uses for the buildings and their landscapes in the future.